The Ordovician sequence of the Builth–Llandrindod Inlier is one of the classic areas of British and world geology. It has been a centre for studies on trilobites since their first description in 1699, from the monographs by Hughes (1962–1979) to Sheldon’s 1987 Nature paper on gradualistic evolution. Over the past 200 years, many of the UK’s leading geologists and palaeontologists have studied the rocks of the area, including Salter, Murchison, Lyell, Gertrude Elles, Nancy Kirk and O. T. Jones.

In recent years, however, it has become clear that the inlier has substantial importance for modern research as well as historical studies, with the discovery of several major sites of exceptional preservation, and most recently the miniaturised Burgess Shale-type fauna of Castle Bank. This aspect will be explored in workshop format, and some of the sites will be visited on field trips (although many are not viable to visit for a large group).

Geological outline

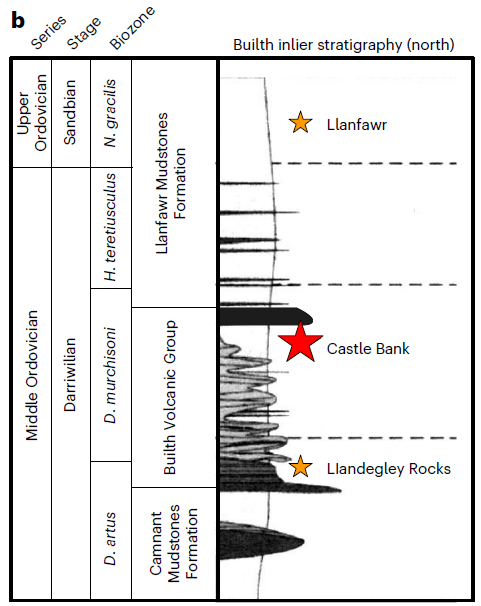

The inlier is Darriwilian (Didymograptus artus Biozone) to early Sandbian (Nemagraptus gracilis Biozone) in age, spanning approximately 10 million years, and occupies a relatively small area of some 50 km2. This window, however, exposes the complete evolution of volcanic island complex, comprising some 2 km thickness of sediments and volcanic rocks. The volcano was triggered by subduction of the Iapetus Ocean beneath Avalonia, and the deposits consist mostly of andesites, dacites and rhyolites with minor baslatic lavas and extensive dolerite intrusions. Most of Wales and much of the Irish Sea were at that time a small back-arc basin (the Welsh Basin), with many volcanic centres during the Ordovician.

The sequence of the inlier starts with fossiliferous siltstones, before the main phase of volcanic eruptions during the late artus Biozone; we believe the largest eruption (the Llandrindod Tuff Formation) represents a caldera-forming event. The murchisoni and lower teretiusculus biozones are composed of a sequence of erosion products and further eruptions (especially in the south), gradually changing from volcanogenic sandstones back through siltstone and ash back into mudstone. This trend continues through the remaining sequence, ending in black mudstones of the Llanfawr Mudstones Formation that are rich in trilobites, graptolites, and sponges. There are fossils at virtually every level of the succession, including many sites with at least some exceptional preservation.

Konservat-Lagerstätten

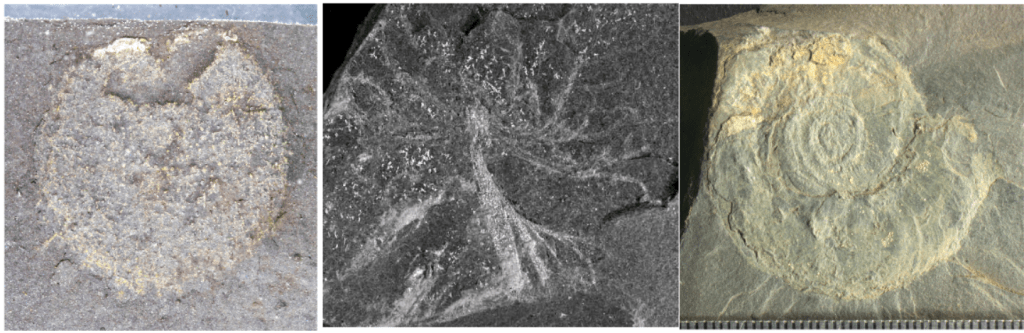

We hope that at least one or two of the exceptionally preserved faunas are familiar, but there are several other deposits, both described and yet-unpublished, that contain an element of remarkable preservation. Complete trilobites are found at virtually every level, and several other localities have yielded complete crinoids, beautifully preserved bryozoans, or sponges. The most remarkable aspect of the inlier’s palaeontological record is the sheer number of significant sites, which integrate into an entire, multi-environmental ecosystem.

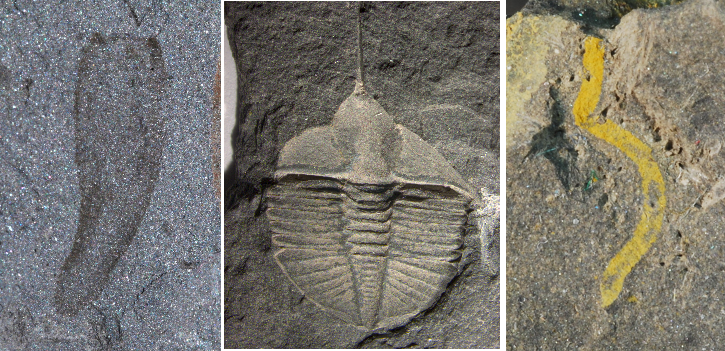

Little Wern (artus Biozone).Only palaeoscolecidan worms have been described so far, but there are also articulated sponges, complete trilobites, and other groups. Exceptional preservation is limited, but the palaeoscolecidans are exquisitely preserved, with multiple taxa known only from this locality (e.g. Wernia, below).

Gilwern Hill Quarry (artus Biozone). Long famous for trilobites (for which it has been worked commercially for decades), there are also a range of rarer but more unusual fossils… from echinoderms (crinoids such as Iocrinus pauli, below, and asterozoans), sponges and fragments of large arthropods. Many of the most interesting specimens are in private hands, but some are in the local museum, or are awaiting description by us!

Llandegley Rocks (artus Biozone). A unique assemblage of shallow-water fossils in silicified volcanogenic sandstone and conglomerate. The most important components are echinoderms and sponges, often preserved in three dimensions and occasionally with silicified soft tissues, but there is also a diverse array of other (mostly biomineralised) fossils. This is a unique fauna from a turbulent, nearshore siliciclastic environment in the Ordovician. (Note: there is a similar, undescribed site with a somewhat different fauna approximately 5 km away.)

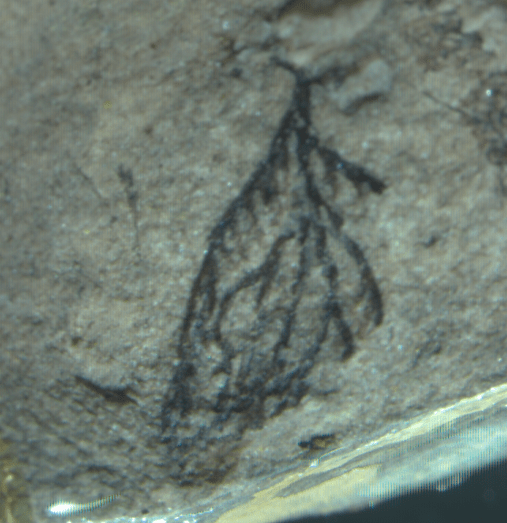

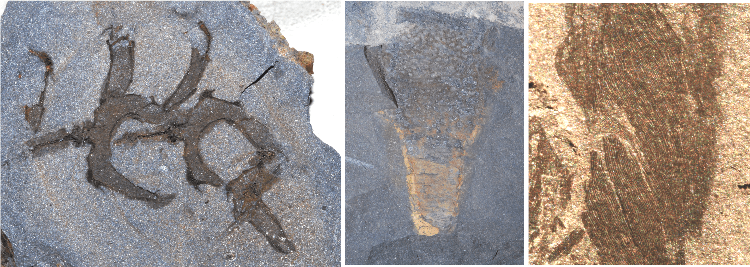

Cwm Brith (murchisoni Biozone). A very unusual fauna in pale ashy siltstone, most notable for diverse dendroid graptolites, but also having yielded complete trilobites, sponges and palaeoscolecidan worms.

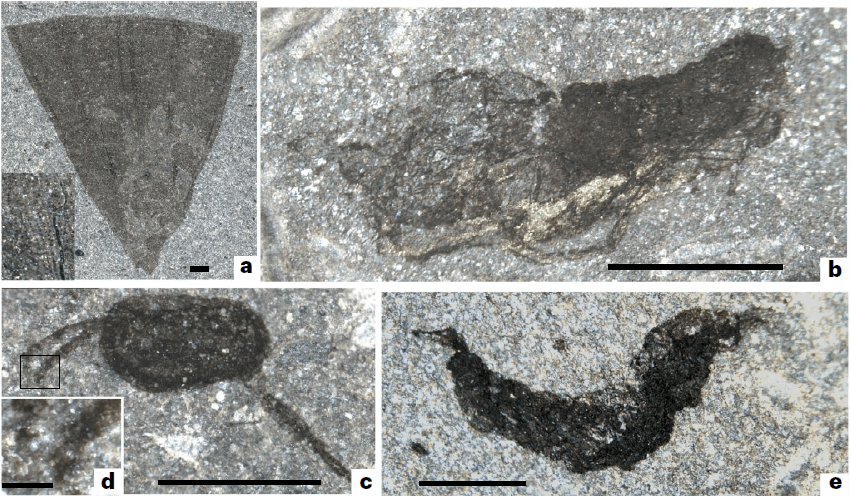

Castle Bank (murchisoni Biozone). Recently discovered Burgess Shale-type fauna with extraordinary preservation of an extremely diverse range of soft-bodied and non-biomineralised organisms including around 20 phyla. Already transforming our knowledge of Ordovician communities, and there is much, much more to come.

Holothurian Bed, Bach-y-Graig (teretiusculus Biozone). Although the holothurians themselves remain ambiguous, the fauna also includes numerous sponges, stylophoran and solutan echinoderms, palaeoscolecid worms and other fossils. Only traces of soft-tissue preservation, but still a remarkable fauna, much of which is still to be formally described.

Bailey Einon (teretiusculus Biozone). A glacially reworked deposit with blocks containing abundant and diverse trilobite, often fully articulated, combined with stylophoran echinoderms, sponges, unique palaeoscolecidan worms and other some other exceptionally preserved taxa.

Dan-y-Graig (teretiusculus–gracilis biozones). An undescribed site with complete trilobites, sponges, rare echinoderms and other fossils. The sponge fauna is less well preserved than some other sites, but nonetheless interesting, and unique.

Llanfawr (gracilis Biozone). A complex of quarries with abundant exceptional preservation of sponges, trilobites and sometimes other groups. One level, the Llanfawr Lagerstatte, is an interval of black mudstone containing a pyritised, sponge-dominated fauna and a range of other minor groups including worms, arthropod remains and an early encrusting fauna on nautiloid shells.